/

RSS Feed

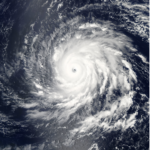

This episode is part 2 of our 3-part series on disaster communication, where we are discussing the book The Devil Never Sleeps: Learning to Live in an Age of Disaster, by Juliette Kayyem. In part 1 we talked about the barriers that make comprehending and communicating about crisis challenging. In this episode, using cases such as Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon explosion, we address how to overcome those barriers and get quality info to the people who need it. The first step is listening downward, or gathering info from people who are closest to disaster.

Sources and further reading

- Baniya, Sweta. 2022. “Transnational Assemblages in Disaster Response: Networked Communities, Technologies, and Coalitional Actions during Global Disasters.” Technical Communication Quarterly 1–17.

- Berg, P. 2016. Deepwater Horizon. Summit Entertainment.

- “Deepwater Horizon.” 2022. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deepwater_Horizon

- Frost, Erin A. 2013. “Transcultural Risk Communication on Dauphin Island: An Analysis of Ironically Located Responses to the Deepwater Horizon Disaster.” Technical Communication Quarterly 22(1):50–66. doi: 10.1080/10572252.2013.726483.

- Kayyem, Juliette. 2022. The Devil Never Sleeps: Learning to Live in an Age of Disasters. PublicAffairs.

- McKay, A. 2021. Don’t Look Up. Netflix.

- Potts, Liza. 2013. Social Media in Disaster Response: How Experience Architects Can Build for Participation. New York: Routledge.

- Sauer, Beverly. 1998. “Embodied Knowledge: The Textual Representation of Embodied Sensory Information in a Dynamic and Uncertain Material Environment.” Written Communication 15(2):131–69.

- Twitter is Going Great! (2022). https://twitterisgoinggreat.com

Transcript

| A | Hi, I’m Abi. You’re listening to TC Talk, where I talk Tech Comm with my husband Benton. I’m a professor, and he’s not, but he’s an all-around interesting guy so our goal is to make stuff relevant whether or not you’re an academic. This episode is part 2 of 3 on Disaster Communication, where we are discussing the book The Devil Never Sleeps: Learning to Live in an Age of Disaster, by Juliette Kayyem. If you missed part 1, We talked about how most organizations focus on preventing disaster, but don’t prepare for the aftermath of disaster when it inevitably does hit. We talked about the cognitive biases that make disaster so difficult to comprehend and communicate about. In this episode, we go over ways that leaders and communicators can get audiences to listen. And, the first step isn’t communicating at all, but listening. |

| B | And now for a topic that I love very much, leadership. “I’ll begin with a few observations on a subject that is both near and dear to my heart. Leadership.” I think this is into her next chapter or she talks about what’s the word. |

| A | What is the word? |

| B | What’s the word. W T W in kids texting nowadays. |

| A | Are you sure that’s a thing? |

| B | What’s going on. It was in the book. |

| A | Oh, |

| B | So she told the story about her her son, didn’t know what he was gonna do that day and texted WTW to his friends. And then someone had an idea and then they all knew want to do. She dragged that metaphor in into her world. |

| A | Who is she speaking to? |

| B | Disaster response leaders. |

| A | Okay. |

| B | But, you know, it’s kind of the communication piece. You have to get the information that’s necessary, communicated to you as the leader. |

| A | You need to get the right stuff. |

| B | You need to get the right information. And you then also need to communicate the right information to everyone who needs to know. |

| A | I actually have a connection to my scholarly reading. May I interject? |

| B | Go ahead. |

| A | Okay. So Liza Potts in Social Media in Disaster Response. She organizes the book by talking about information as compared to data as compared to knowledge. And the specific cases she’s looking at are, after disasters, shootings or bombings or hurricanes, one of the key pieces of information that people are looking for is who is safe, who is injured, who is dead, right? And in the case of Hurricane Katrina, this was in |

| B | 2005. |

| A | Thank you. So I mean, there was absolutely a social element to the web at that point. But she was talking about like the official CNN People Finder or something. And it was a webpage that was not usable. |

| B | Go figure. |

| A | And there was no way to edit information or verify information. You simply had to email like the hurricane help desk in order to say, Oh, here’s some information about my loved one. So it was a very closed system. And as a result, it stayed at that level of information. Oh wait, data to knowledge to oh, shit. Or no, no, no. It was data information knowledge I think. Data is decontextualized bits of information. Information is validated data. Knowledge is once you take that information and redistribute it out to the people who need it. That’s the way that she defines those. So, it was decontextualized, it was unable to be verified. There was not a mechanism for getting the information out to the people who needed it. Basically her whole argument is that if we want to get knowledge to people than we need to open up our channels to more participation. We are way past the point of gatekeeping this kind of thing. People are, people are going to do it anyway. So the role of technical communicators and experience architects and user experience professionals is to think about how people are going to use multiple technologies, multiple tools. And how can we streamline the full experience, not just their use of say, one app? How can we kind of pull this together? So when I say people are gonna do this anyway, people started using Craigslist for Hurricane Katrina. |

| B | Wow. |

| A | The Lost and Found section. |

| B | Oh man. |

| A | I know. Now as you can imagine, that wasn’t ideal in a lot of ways. |

| B | Oh man, anyone who has used Craigslist knows that it has not fundamentally changed since Hurricane Katrina. |

| A | Exactly. So there was some shady stuff going on there, but it reflects the fact that people are going to use the tools they already know how to use. And then Potts also talks about how Google created a People Finder. So Google was poised to be like the one list to rule them all. But I think they went a little too far in the other direction where there weren’t enough mechanisms for moderation and verification and they got overrun with shit posting. Which sadly, you have to expect people to abuse a system in any way they possibly can. But the failure of that doesn’t rule out the need for us to consider ways to turn data into knowledge by using people who are closest to the disaster themselves. Not gatekeeping the communication. So you’re talking about leadership. I don’t know how much Kayyem addresses this, but it seems to me that a big piece of that would be humility, willingness to listen, and creating venues for collecting information. |

| B | So in “What’s the Word,” it’s all about in terms of disaster, knowing what is going on. So firefighters have a saying, “Know what your fire is doing at all times.” |

| A | Your own personal fire. |

| B | Yes. This highlights the importance of situational awareness. Have you encountered that term before? |

| A | No. But I suspect it’s not dissimilar to what Beverly Sauer calls pit sense. She was the scholar I was telling you about, who studied miners. M I N E R S. |

| B | Yes. |

| A | And was commenting on this sort of embodied knowledge that they have. |

| B | It sounds like intuition. |

| A | Yeah, somewhat. |

| B | Workplace intuition. I just felt it or I just I just knew. I can’t say how I knew, but |

| A | Yeah, so an example might be if there’s like shifting of the earth. You can’t necessarily read how to sense that out of a textbook. But yeah, I mean, the more situationally aware the miners are, the safer they are. They may not know what embodied knowledge they’re applying in a given moment, but it’s real. Is that in any way related to what you’re talking about? |

| B | Yes. Situational awareness, it is a regular refrain in military parlance. You, we talk about it at, at work, you know, trimming trees. Situational awareness means not only knowing where the guy in the bucket is so you’re not underneath him when he’s cut cutting a branch off. But also knowing what the terrain is like that you’re walking on so you don’t hurt yourself. Being aware of where people might be coming into your job site so that you can keep them from getting hurt. |

| A | So it’s kind of like this implicit embodied knowledge, but it’s being more intentional about it? |

| B | Yes. |

| A | Okay. |

| B | It’s more intentional and less like quasi intuitive. Situational awareness is a formalized thing in the way that she was talking about it. So she describes it as the “memorialization or record of events as they occur over time and location, what that data means, and what needs to happen to respond at that moment. It’s also predictive, attempting to document what may happen next and what will be needed.” The three general parts of situational awareness, are perception: what is happening. Comprehension: what it means, and projection: what may likely happen. |

| A | Is this like a genre? Like it sounds like something that gets put in writing. |

| B | Yes. There’s a lot of different forms that it could take. It could be it could be like a database entry form. It could go from highly formal to highly informal. So a little bit of a change in topic again. |

| A | You got to work on your transitions, dude. |

| B | I gotta work on my transitions. So that sounds like a pretty obvious thing, right? Well, yeah, of course. Kayyem regularly said that this field is not rocket science. There’s nothing highly complicated or esoteric about disaster management. |

| A | Once you get humans involved though, I don’t know how we could not be complex. But yeah, go ahead. |

| B | The psychology part, though. And pundits, influencers, and other traditionally popular media and social media sources, are typically not up to the task of communicating crisis information. Often, official channels are better than the typical media and social media at communicating crisis information. But just as often they are not. Example being during Katrina, as the levees were being breached, the Bush administration was saying, everything’s fine because they didn’t know. Not because they were purposely lying. |

| A | Well, |

| B | I wouldn’t put it past them. I wouldn’t put it past them, but they were getting information from a further away part of town and I haven’t been in a hurricane, but it’s a rainstorm. So that more formal has its own pitfalls. Like you were saying with the Potts example, official channels for communication do not always do a good job. Kayyem said that greater openness to less formal information collection may increase vulnerability to misinformation. |

| A | Yes. |

| B | But it also increases the ability to pick up critical information early. |

| A | Ooh. |

| B | So one example of that early pickup of critical information is around COVID. So San Francisco Mayor London Breed, awesome name. Just got to say it, got ahead of the curve by hearing the silence of the Chinese New Year celebrations in her city in 2020, which is when it was all going down. People in the Chinese community in the city had connections back home to people in China. And they were hearing from people in China that this is serious. And they didn’t go to the Chinese New Year celebration in San Francisco. Mayor London Breed sees that the celebrations are not nearly what they normally were. And she realized these are the people who would know. And as a result, they successfully shut down and ramped up precautions ahead of most of the country. When managers are quicker to listen upwards than downwards, they’re more likely to create a Challenger. |

| A | A Challenger? |

| B | The shuttle that exploded. |

| A | Oh yes. You want to listen to those engineers. |

| B | The people who know what they’re doing, the people who know what’s happening, the people who are closest to the action are the ones with credibility, not the ones with chief in their title. It just seemed like a great thing to linger on. |

| A | I would drop the mic, but that would be loud. |

| B | No, let’s not do that. That would be counterproductive for the remainder of our podcasting. I mean, in a situation like that, I could I could easily see the mayor of San Francisco Saying that there is no writing on the wall. There’s, it’s not coming. We’re going to add zero cases. Gosh, you remember that? Wasn’t that just comical? |

| A | Hey. Okay. Do you remember Elon Musk’s postings about it? |

| B | I don’t. I hope someone archived it. |

| A | He was like, this is nothing. This is no big deal. That’s I think the perfect example of someone who needs to stay in their lane. |

| B | Yes. Absolufuckinglutely, yes. Elon Musk needs to stay in his lane. He is a good engineer and he is a shitty everything else. |

| A | But being a billionaire, I guess just magically confers all the knowledge of the Universe on you. |

| B | So because I’m such a good transitioner, let’s Just transition. |

| A | You’re like the student who writes next, |

| B | Next |

| A | and then goes to a completely new topic. |

| B | Yes. Kayyem goes on to talk about Cassandra. Cassandra’s curse, which typically is visited upon those who are saying that there’s disaster lurking, Chicken Little style. You’re familiar with |

| A | Greek mythology. |

| B | Greek mythology. Cassandra, for those of you who aren’t, is a prophetess who was always right in her predictions. |

| A | But no one believed her, |

| B | But no one believed her. |

| A | I think that’s called being a woman in a horror movie. |

| B | Or being a woman in the horror movie that is the American experience. |

| A | Ah. I was thinking Alien, but that works too. |

| B | So ways to overcome Cassandra’s curse are to speak directly. |

| A | Like Jennifer Lawrence in Don’t look up, we’re all going to fucking die. |

| B | Yes. |

| A | Ah, okay. |

| B | That’s it. |

| A | They didn’t really take them seriously anyway but point taken. |

| B | True. It was direct but another important thing is to make the improbable familiar. We’re all going to fucking die is improbable. So figuring out a way to make it familiar is a challenge for someone who is talking about a real disaster that hasn’t been experienced by people who are in its way. For those in leadership, communicating about a crisis must, must address two main needs. Numbers and hope. |

| A | Oh. And we’re all going to fucking die does not contain much room for that, yeah. |

| B | It does not communicate much hope. |

| A | The numbers surprises me though. Tell me more about that. |

| B | Communication in crisis is largely helping people not panic, right? You need to have hope to give people. So that’s the, that’s the qualitative part. And then the quantitative is focusing on like, okay, it isn’t a mysterious, things are bad. It is currently X bad. But we have this plan to enact Y so that we get X down to less than X. |

| A | Yeah. |

| B | The military calls this strategy in situational awareness BLUF. It’s an acronym as is everything in the military. Bottom line up front. |

| A | Can I steal that for my tech comm courses? |

| B | Yes. |

| A | Thanks, military. |

| B | Yeah. I would say that the Internet has another acronym for it, TL;DR. TLDR for those of you not familiar is |

| A | Too long, didn’t read. |

| B | Yes, is that. I was going to get there but apparently you wanted to make a meta-joke in the middle of the definition. |

| A | TLDL. Too long, didn’t listen. |

| B | But all of this relies heavily upon having a good information gathering and reporting system. |

| A | Like we were talking about with Hurricane Katrina. |

| B | Yes. Having not enough eyes is a problem. |

| A | Although in the case of a hurricane, one eye is enough. |

| B | Ooh. So establishing the system is not something you want to try to do while the sky is falling. A good Sit Rep, or situational report, which, you know, kinda flows naturally out of situational awareness, lays out not only the situation, but also the continuity. As in, we’ll be back this same time tomorrow for an update. |

| A | That makes a lot of sense. You don’t want to leave people hanging. |

| B | Right. Another key piece is that it must be shared with all relevant parties. |

| A | Transparency. |

| B | Transparency. And this throws out the “need to know” concept from intelligence agencies. |

| A | Oh. |

| B | I mean, I guess it takes that same concept and expands it to include everyone who could be affected. |

| A | Great, all stakeholders. |

| B | Important in this is translation. If you’ve got a large community that does not speak English, they need to know if there’s a disaster coming to. We don’t need to be like, Oh gosh, yeah, let’s get the translators, the Spanish translator, and oh and the Hmong translator. Who else have we got around here? We’ve got? What I’m getting at there is that is a system that you need to have in place so that you can hit go on a button and it like, |

| A | But have a lot of failsafes in place. So you don’t send out a Hawaii Missile Crisis that is not real. |

| B | That’s a really good one. |

| A | Yeah. It seems to me that the more common climate-related disaster becomes the most vulnerable people are hit first, hit the hardest. And we don’t necessarily have a way of accounting for that. |

| B | Absolutely correct. There is a term for that, and it is climate justice, which itself is a subset of something called environmental justice. Environmental justice also looks at the ways that, say, industry, pollution from industry, affects underserved populations. |

| A | The pipelines. |

| B | Yes. |

| A | And another example that I read about this comes from Sweta Baniya wrote an article for TCQ in 2022. She builds on a lot of the work by Potts that I talked about earlier in this conversation about the value of making systems open and allowing the affected people to contribute to data gathering and validating and that kind of thing. And Baniya, I think, brings in a really important point, which is that this work must be done with a social justice lens because of, like I said, this disproportionate impact. Look at Puerto Rico and Hurricane Maria. |

| B | Mm-hmm. |

| A | She comments on how we have to understand the colonialist history of Puerto Rico and its lack of resources as caused by the US government. |

| B | Extractive industry as well. |

| A | Yes. Capitalism, what have you. So she says “there’s an urgency in the field of TPC, technical and professional communication to pay attention to how non-Western decolonial rhetorical knowledge, traditions, and global TPC help to address social injustices. As the world’s most vulnerable populations continuously suffer through environmental and other crises, decolonial methods center those affected communities and their voices and uplift their voices and their needs.” So it seems to me that part of a disaster preparedness plan like you’re talking about would involve having the structures in place before the disaster happens, but being intentional about those structures so that it’s not just a one-way flow of communication or that it’s prioritizing one narrative. |

| B | Absolutely. That is another thing that you gain from building the system when there’s not a crisis, is that you have time to think of these things instead of scrambling. So as we’re talking about like making sure that we are getting the information that is needed out to everyone. That’s an important priority. Because we value everyone. And this is a really ugly transition. |

| A | You’re trying. |

| B | Because structures and finance are a major statement of values and priorities. |

| A | Thank you. Good effort. |

| B | Like there’s, there’s innumerable ways that people have said it. That talk is one thing, but what are you putting behind your talk? Your budget is your value statement. That actually does flow nicely into her next chapter about getting everyone on the same page about disaster prevention and preparedness. So it is very typical that a major event will spur organizations to create a new position or department in response. Like 9/11, |

| A | Department of Homeland Security. |

| B | the Department of Homeland Security. But in private corporations, they would create a Chief Security Officer. See, we care about security too here at Company XYZ. A major hack, you get a Chief Information Security Officer. More often than not though, these added folks are treated like a separate entity that’s really just there to make everyone feel good. |

| A | That kinda makes me think of people in like, Chief Diversity Officer type positions. |

| B | Oh, yeah. |

| A | Unfortunately. |

| B | Nobody wants to have to actually change what they’re doing. They just want the warm fuzzies of saying, See, we did something. |

| A | Let me see if I’ve got this right. By tacking on a position or an office strictly to deal with disasters, that means that the philosophy isn’t integrated throughout the organization. |

| B | Bingo. That’s exactly right. So if you’ve got a chief information security officer and then you don’t give them the ability to say, we’ve gotta do multi-factor authentication on everything. Everybody hates multi-factor authentication except the IT nerds. But if you create a position for someone to increase your security, |

| A | It needs authority behind it. |

| B | If you don’t have an integrated company culture acceptance of this need to change, none of it matters. |

| A | It seems like a waste of a good opportunity. |

| B | It does. And I mean, I’ve been at companies where exactly this sort of thing happens. When a change comes along, it’s a groaner for everyone. It’s big on promise and then it It’s headache on delivery. |

| A | The first company I worked at out of college was acquired by a global company and they imposed a new dress code. There was rioting in the cubicles because people couldn’t wear pajama pants to work anymore. |

| B | Terrible. |

| A | Yeah, and it didn’t help that the local president was like, y’all can keep wearing your pajama pants, just keep it on the down low. |

| B | Where else would you wear the pajama pants? Up on your head? |

| A | Yes. You’d wear pajama pants on your lower half. |

| B | Dad joke strikes again. |

| A | And at work apparently. And that was an inconsequential policy. But witnessing that push-back, I can definitely see how it would be hard to integrate the kinds of attitudes needed for disaster preparedness and response into a company. |

| B | What it really all comes down to in this integration thing is disconnects. Disconnects between upper management and frontline workers, disconnect between different departments. As I’d mentioned, whether its demands from the sales team or corporate, it seems much too common that people who have authority to make a change in how things are done, they know what’s gotta be done. |

| A | Top-down. |

| B | They don’t know. Yeah. They went in reality, they don’t know what the what the frontline situation is. |

| A | And their goals are primarily economic. |

| B | Their goals are primarily economic, efficiency. Squeeze all we can out of our labor dollars. Even when the ideas are something I would agree with, it’s rare that leadership has any idea what the functional impact of a change is, let alone that they would provide support for that change. |

| A | I’m looking at you higher ed. |

| B | A great idea from on high and then it really just amounts to extra duties piled onto your normal extra duties. Let’s carve this many hours out of your out of your weekly schedule or your weekly production so that you can address this issue. That’s not what they do. This support could be training, modified expectations, increased headcount. Boy, increased headcount, does a whole lot to |

| A | You mean more employees? |

| B | Yes. |

| A | What a weird disembodied way to describe it. Is that like corporate lingo? |

| B | It is. |

| A | Oh no and I thought human resources was bad. |

| B | Yes. We need to mine the human resources better. Yes. |

| A | Like the sign by the McDonald’s. Now hiring smiling faces. Forget the rest of the human. |

| B | Kayyem’s next chapter is all about avoiding the last line of defense trap. This is where we start to talk about Deepwater Horizon. Buckle up. We’re going deep. |

| A | Okay. |

| B | So the Deepwater Horizon was in the Gulf of Mexico. It was an oil rig that was a floating platform oil drill that was being put into production. It exploded and it made the largest oil spill in American history. By a lot. 11 people died and 17 people were injured. |

| A | And it was being run by BP, right? |

| B | It was, yes. It was being run by BP, British Petroleum. This was in 2010. |

| A | Okay. |

| B | So those are two separate disasters. There’s the explosion and there’s fucking up a major body of water for months. |

| A | And the cleanup efforts and |

| B | This was from the Wikipedia page on the explosion. “The US Coast Guard had issued pollution citations for Deepwater Horizon 18 times between 2000 and 2010, and had investigated 16 fires and other incidents.” This is the part that just kills me. “These incidents were considered typical for a gulf platform and were not connected to the April 2010 explosion and spill.” Pollution citations 18 times over ten years and 16 fires and other incidents. But that’s all normal for the industry. |

| A | Oh. |

| B | It kinda makes you think we need to stop this industry, doesn’t it? |

| A | Yeah. |

| B | Yeah. I think that we ought to just bury them. Bury them all. Maybe in a hole in the ground? |

| A | Until they turn into fossils? |

| B | Yeah. |

| A | And then we can extract them? Sorry. |

| B | Turnabout is fair play. There is also a movie that was done like six years later. I watched that movie. But I wasn’t able to find any discussion on how the details in the movie lined up with reality. |

| A | You don’t know how much creative license they took. |

| B | Right. But there’s a point where Mark Wahlberg’s character fumes at the BP management onsite, listing off more than a dozen systems that weren’t functioning properly from the top of his head. Beyond that, Halliburton, the contractor that poured the concrete for the well, did not run the cement bond log. |

| A | Hate when that happens. |

| B | Yeah. |

| A | Cement bond log? |

| B | Yes. |

| A | I don’t know why I’m laughing at that. |

| B | It is an odd string of words. True. But that’s, that’s like testing to see that their cement is cured, is going to hold together. Again, this is from Wikipedia, the Department of the Interior “Exempted BP’s Gulf of Mexico drilling operation from a detailed environmental impact study after concluding that a massive oil spill was unlikely based on the plan submitted in February of 2009. In addition, following a loosening of regulations in 2008 BP was not required to file a detailed blowout plan. The BP well had, had been fitted with a blowout preventer. |

| A | I wish they had those for new parents. |

| B | That’s a different kind of disaster. |

| A | Proceed. |

| B | Different kind of blow out. “But it was not fitted with remote control or acoustically activated triggers for use in case of an emergency requiring a platform to be evacuated.” |

| A | Okay. Is it, okay, is it just me or does it seem like all of these disasters did not happen out of the blue? That |

| B | Most don’t. Most disasters do not happen out of the blue. The explosion of the Deepwater Horizon is really a story about cutting corners so much and so often that they ended up with a circle and they kept trying to cut corners off of the circle. The point that the author was making about the last line of defense trap though, is about the blowout protector. This is a five story tall 400-ton piece of equipment on the ocean floor that is supposed to pinch the pipe shut when there’s trouble. It has one job. There were six automatic triggers. not manual, with different ways that it should have been activated. None of them worked. |

| A | Fuck. This does remind me of the Titanic and its fancy partitions. |

| B | It could have been ordered with a remote activation system, but it wasn’t. So as the rig was in flames, workers were in the control room trying to turn the well off. It’s not clear if the system ever activated even with the workers’ heroism. The investigation revealed that many elements of a blowout protector are not actually designed to withstand and operate in exactly the conditions when it is needed. |

| A | Then what’s the point? |

| B | Warm fuzzies, right. After the oil spill, there was a congressional investigation. One of the things that is not designed into a blow-out protector, which you think it would be, 400 fucking tons of it, is the ability for it to pinch off any grade of pipe that is going through it. |

| A | That seems like a no-brainer. |

| B | You don’t really have time when there’s a blowout coming to be like, Oh, let’s calibrate it to the right pipe we have now. It’s gotta be ready to hit at a moment’s notice. Another thing is that the RAM is not, or it’s less likely to be effective when there are like vibrations and torsion and all of the kinds of things you would expect to happen when shit is going sideways. If you test one element at a time, it does as advertised. But if you layer things on to become reality, it just cannot cope with that. |

| A | Yes. Good way of putting it. |

| B | Her point on it, is that we need to be prepared for the last line of defense to fail. She mentions that an FMEA, which is a failure modes and effects analysis, is what design is supposed to do to identify all the things that could go wrong and what effect each would have if they did. |

| A | Okay, can I jump in with a potentially relevant example? |

| B | Yeah |

| A | I saw this on Twitter. |

| B | Sounds good. Twitter is doing great right now. |

| A | Yes. Twitter is going great Dot-com. Yeah, as we speak, Elon is throwing Twitter in the trash. And I saw that in the internal documents about the Twitter Blue, you know this like buy your verification check mark scheme, by Musk |

| B | Scheme. Yep. |

| A | The sections about how can people abuse this or what could go wrong were blank. Again, given the credibility of Twitter, I don’t know that that’s true, but it’s plausible. So is it kinda like that? |

| B | Yeah, I guess kind of, but it’s rigorous and it’s like numeric. I have actually worked on one of these documents myself, and I can attest to the fact that they are no fun. You may have to work in a cross-functional team on it with all the joy involved in a group project. And it is a very different task from the engineering used to create a design. It requires substantially different types of creativity about what could go wrong than an engineer is used to in their daily tasks. |

| A | It seems to me like a technical communicator would be a great team member when it comes to those documents. |

| B | Quite possibly, yeah. TLDR on FMEAs. |

| A | BLUF. |

| B | Is that they are no fun to work on and it is hard to do well, if it is only occasionally part of what you do. Clearly, this blowout protector did not have a good FMEA performed. I would even go further and say that BP didn’t perform its own FMEA on the site as a whole. Because the numerous efforts to cap the well over the next several months, several months, that oil was just |

| A | pouring out. |

| B | pouring out into the ocean. These efforts in no way communicated “We’ve got this.” One last gem I wanted to bring up from the movie was that Mark Wahlberg’s character. He’s talking about noodling with one of the other characters in the film. And noodling is when you, |

| A | Is this where you stick your hand in a hole in a river and try to grab out a fish? |

| B | Yes. You’re right. |

| A | Because I saw a video and it was terrifying. |

| B | He talks about noodling. You go in, expecting to get bit. Hope isn’t a tactic. It was the perfect encapsulation of the whole event. |

| A | There’s actually some work on this in tech comm, |

| B | Really? |

| A | Yeah. Erin Frost wrote a piece about the communication after the disaster and its effects on Dauphin island which was like one of the communities that was hardest hit by the effects of this oil spill. |

| B | I’d imagine. An island, all you’ve got is coastline and. |

| A | Yep. And she compared the communication by like BP and the communication by community members. And it was just another reminder to, like you were saying before, communication needs to account for all stakeholders. And whereas the more official corporate communication was focused very much on economics, community members focused more on economics, but also the environment and things that matter beyond money. |

| B | It’s almost like the things that matter are all beyond money. |